Charlie Russell’s Top 5 Art Pieces That Capture the Spirit of the Wild West

If you've ever stood in front of a Charlie Russell painting, you know there's something electric about his work. It's not just the detail—the powerful horses, the sweeping Montana skies, the grit of cowboy life—it’s the feeling that you’re standing inside a story. Russell wasn’t just painting the West; he lived it.

Nicknamed “the Cowboy Artist,” Charles Marion Russell (1864–1926) created over 4,000 works that celebrate, mourn, and immortalize the American frontier. From Indigenous warriors to outlaw raids, stampeding cattle to quiet winter nights, his work captures both the myth and the reality of the West.

Let’s explore five of his most iconic masterpieces—each one a window into a world that’s long gone, but never forgotten.

1. The Hold Up (1899)

Also known as “20 Miles to Deadwood”

This is Western drama at its best. A stagecoach barrels through a wooded trail—until bandits bring it to a halt. Guns are drawn. Tension fills the air. Russell captures the chaos of the moment, but never loses sight of the detail: the dust in the air, the fear on the passengers’ faces, the sheer power of the horses.

Why it’s iconic:

-

One of Russell’s most valuable pieces—fetching millions at auction.

-

It perfectly blends realism and storytelling.

-

It’s the cinematic Western before Hollywood ever arrived.

2. Piegans (1918)

“Piegans” shows a group of Native American riders moving across a snow-covered prairie—quiet, proud, and strong. There’s no action here, just presence. It’s a powerful tribute to the Piegan people, a band of the Blackfeet Nation, whom Russell deeply respected.

Why it stands out:

-

Honors Indigenous identity with dignity and grace.

-

The composition is cinematic, with sky and land stretching endlessly.

-

A reminder of the human connection to land and tradition.

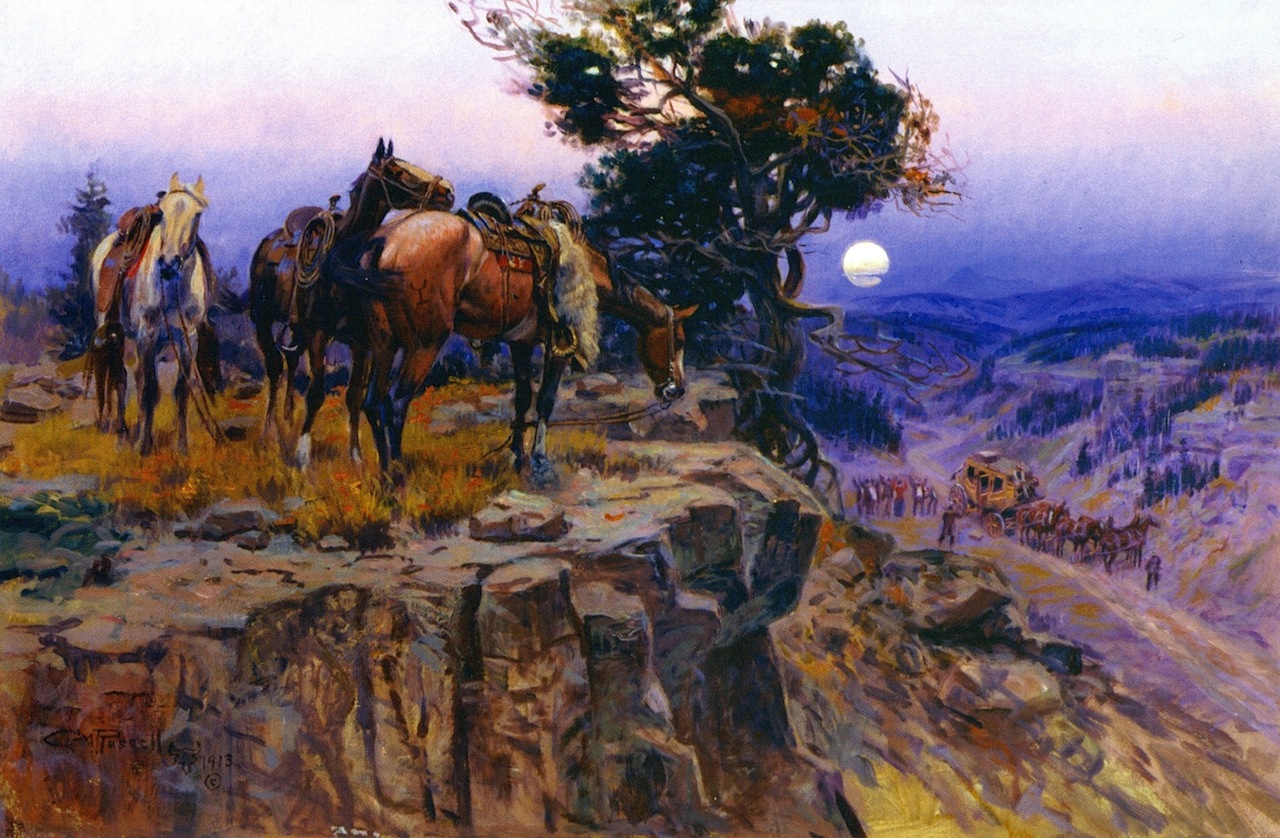

3. The Horse Thieves (1901)

Russell never shied away from the darker edges of frontier life. In this moonlit scene, a band of warriors rides away with stolen horses. There’s danger, movement, and mystery—all captured in silvery light.

What makes it a masterpiece:

-

Masterful use of light and shadow.

-

Captures a true story of conflict and survival.

-

Evokes the tension and lawlessness of the Old West.

4. In Without Knocking (1909)

This painting is full of energy. A cowboy bursts into a saloon—doors swinging, hats flying, chaos unfolding. It’s a slice of life from the untamed frontier, and a perfect example of Russell’s storytelling flair.

Why it resonates:

-

Bursting with personality and motion.

-

Detailed portrayal of daily Western life.

-

A reminder that Russell had a sense of humor as well as a sense of history.

5. Waiting for a Chinook (a.k.a. “The Last of Five Thousand”)

or

When the Land Belonged to God

This one’s a tie—because both reveal Russell at his most reflective.

“Waiting for a Chinook” is haunting. A lone cow stands starving in a harsh winter, wolves circling. It’s quiet and bleak—and unforgettable. Painted early in his career, this piece showed Russell’s deep empathy for both animals and the rugged land.

On the other hand, “When the Land Belonged to God” portrays a wild, untouched landscape teeming with wildlife. No humans. No fences. Just nature in its original state.

Why these matter:

-

Show Russell’s emotional and environmental depth.

-

Express loss, solitude, and reverence.

-

Remind us of what was sacrificed during westward expansion.

Final Thoughts: Why Russell Still Rides High

Charlie Russell didn’t paint legends. He painted life. He gave us stories, not just scenes. He gave voice to people often overlooked—cowboys, Native Americans, ranchers, and animals—and let the land speak for itself.

His work isn’t just nostalgic; it’s honest. It reflects the beauty, brutality, humor, and heartbreak of a place in time that shaped American identity. And somehow, 100 years later, it still feels relevant.

If you ever get the chance to see his work in person—especially at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana—take it. Until then, let his brush guide you through a West that’s long gone but never forgotten.